Discrete Homotopy Theory, pt. 1

I learned about something really cool yesterday and now I feel the need to share it.

I learned about a really new field of math called Discrete Homotopy Theory. This is a homotopy theory for simple graphs that seems different than the classical homotopy theory of graphs thought of as CW complexes. Fascinatingly, there turn out to be two “exotic” homotopy theories for undirected graphs. One of them is called \(\times\)-homotopy theory. This paper gives a pretty good introduction to it. The other is called discrete homotopy theory or A-homotopy theory[^1]. I’m going to talk about this one for this post, simply because I haven’t gotten the time yet to investigate \(\times\)-homotopy theory!

The first thing we must always do when talking about graphs is figure out which category of graphs we are working in. For discrete homotopy theory, this category[^2] is \(\mathbf{Gr}_{r}\). This is the category whose objects are sets equipped with binary, symmetric, reflexive relations, and whose morphisms are functions that preserve the relation. The category for \(\times\)-directed homotopy theory is \(\mathbf{Gr}_{\ell}\), the category of loop graphs, i.e. those graphs that can have loops. The category \(\mathbf{Gr}_{r}\) is a full subcategory of \(\mathbf{Gr}_{\ell}\) on those graphs where every vertex has a loop.

We can think of the objects of this category as simple graphs where morphisms can collapse edges. This category is a quasitopos, with a nice discussion about this on the nlab. We are going to refer to the objects of \(\mathbf{Gr}_r\) simply as graphs.

Given two graphs \(G\) and \(H\), let \(G \square H\) denote the box product. In other words, this is the graph with \(V(G \square H) = V(G) \times V(H)\) and where there is an edge \((g,h)(g',h')\) if there is an edge \(gg'\) and \(h=h'\) or \(g=g'\) and there is an edge \(hh'\). Note that this is not the categorical product in \(\mathbf{Gr}_r\). However it is a symmetric monoidal closed product[^3]!

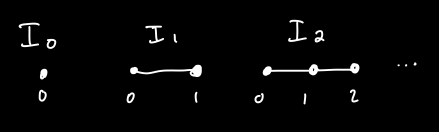

Let \(I_n\) denote the interval graph on \(n+1\) vertices.

Let \(f, g: G \to H\) be maps of graphs in \(\mathbf{Gr}_{r}\). An A-homotopy between \(f\) and \(g\) is a map \(h: G \square I_n \to H\) for some \(n \geq 0\) such that \(h(-,0) = f\) and \(h(-,n) = g\). So there is some similarity with classical homotopy theory, but we are allowed to have a whole bunch of different interval objects, and any of one them works.

Now its easy to define homotopy equivalence. A map \(f: G \to H\) of graphs is an \(A\)-homotopy equivalence if there exists a map \(g : H \to G\) and homotopies \(gf \simeq 1_G\) and \(fg \simeq 1_H\). Okay so here’s a crazy fact: if we let \(C^n\) denote the cycle with \(n\) vertices, then \(C^n\) is contractible if and only if \(n = 3\) or \(4\). This kind of blew my mind when I first saw it, and also made me scratch my head. Why in the world should that be the case.

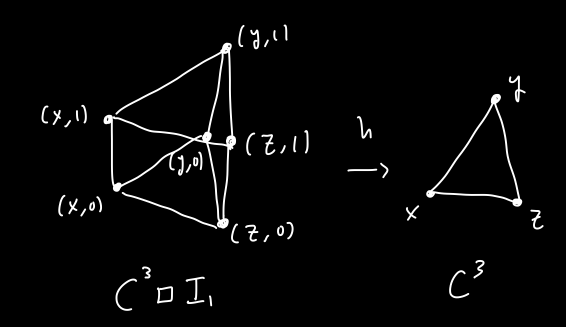

Well the only way to understand it is to work out the example. Let’s draw what a map \(h : C^3 \square I_1 \to C^3\) should look like.

Now remember maps in this category can collapse edges. We want \(h\) to squash all of the top part of \(C^3 \square I_1\) to a single vertex and keep the lower floor as is. This is easy to do, simply map \(h(i,0) = i\) and have \(h(i,1) = (x,1)\) for all \(i \in \{ x , y, z \}\).

This gives a homotopy in one direction, and the other one can be crafted using the same argument, showing that \(C^3\) is null-homotopic, i.e. it is homotopy equivalent to one of its vertices!

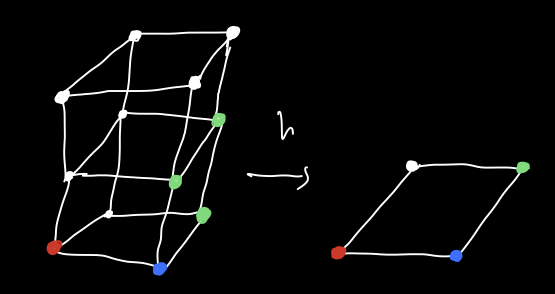

We can do a similar argument for \(C^4\).

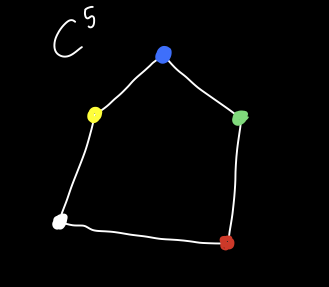

Shockingly, this won’t work for \(C^5\)! Why not? Well, lets take a look at \(C^5\).

In order to collapse \(C^5\) onto a vertex using a homotopy, we have to be able to collapse the white and red vertices. But since they are connected to the yellow and green vertices, those need to be collapsed too. In effect we would need to map the white vertex to the yellow verte and the red to the green vertex, but this can’t happen, because there’s no edge between the yellow vertex and the green vertex!

I don’t think I’ve fully digested how this kind of homotopy theory feels, but there’s some really cool results on this already. For instance, one can equip \(\mathbf{Gr}_r\) with a fibration category structure, proven Kapulkin, Mavinkurve effectively giving it a complete \(\infty\)-category structure. Its currently an open problem if this \(\infty\)-category is equivalent to the typical \(\infty\)-category of spaces! However in that paper, the authors also prove that if we \(1\)-truncate both the \(\infty\)-category of graphs up to \(A\)-weak homotopy equivalence and the \(\infty\)-category of spaces (getting the \(\infty\)-category of groupoids), then they do get an equivalence!

This is super fascinating to me, I’m excited to dig into more of this work when I get the chance.

[^1] Not to be confused with \(A^1\)-homotopy theory from algebraic geometry!

[^2] If you’ve been reading my other posts on categories of graphs, I apologize for the change in notation. I will hopefully write a new post soon enough explaining all that I have learned about the zoo of categories of graphs and why I’ve changed notation. In old posts, I referred to \(\mathbf{Gr}_{r}\) as \(\mathbf{Grph}\).

[^3] In fact, by a lovely result of Kapulkin and Kershaw, the box product and the categorical product are the only symmetric monoidal closed products on \(\mathbf{Gr}_r\)!